When we learn a new skill, we often get feedback on our performance– rewards for good behavior, debriefs from a sports coach, or corrections from a piano teacher while stumbling through our pieces. In general, though, we improve many skills without anyone telling us how we are doing: we know when we’ve made a mistake when we’re practicing a song alone. Our own “internal critic” evaluates and signals our errors, somehow guiding us toward better performance. What in our brains serves the role of this internal critic?

The neuromodulator dopamine plays an important role in this process. In experiments where animals are provided with rewards for good performance during learning, more dopamine is released in the basal ganglia when the animal has a surprisingly successful outcome. However, what happens when there is no actual reward beyond the satisfaction of getting it right?

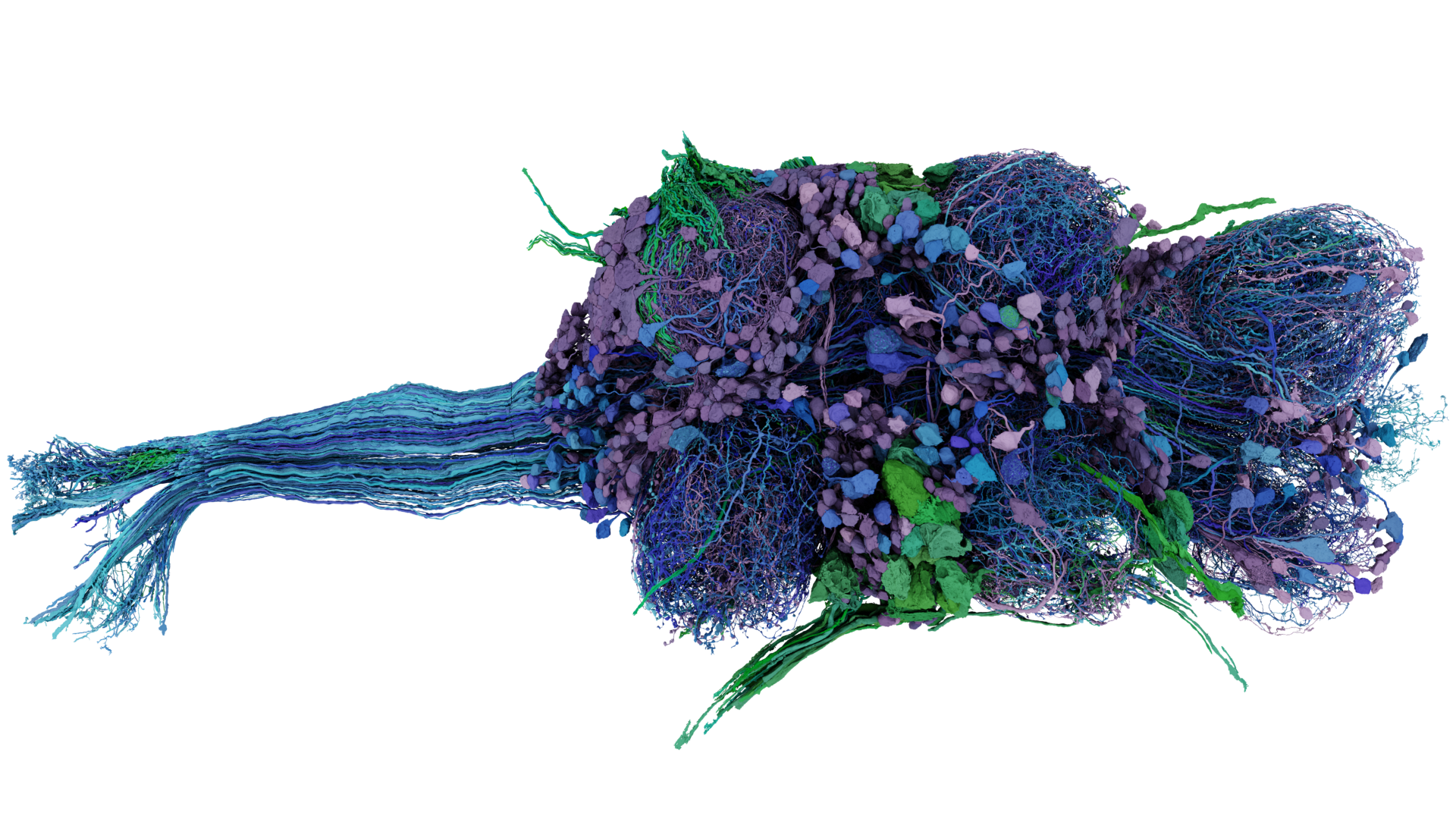

An example from the animal kingdom of such natural trial and error learning is that of birdsong. Baby birds listen to a tutor and memorize a model of the song they will eventually sing. They then practice alone, gradually refining their song and no longer needing the tutor. Songbirds’ brains have isolated regions dedicated to song learning and production, making birds an ideal model system in which to study the biological mechanisms of skill acquisition. Through ongoing collaborations with a number of experimental labs, the Fairhall group in the Department of Neurobiology and Biophysics models many aspects of this system to understand how biological brains carry out trial and error learning.

Photo by: No PEOPLE on Adobe Stock

In a study published in Nature on March 12, Adrienne Fairhall and Fairhall lab member, Alison Duffy, collaborated with Vikram Gadagkar’s lab at Columbia University to study the role of dopamine in song learning. The group tracked song development in juvenile birds while the mature song is taking shape. At the same time, the Gadagkar lab used fiber photometry to record dopamine fluctuations in the basal ganglia during singing. They found that “good” song renditions, those more similar to the eventual adult version of the song, were followed by dopamine activation and “bad” renditions led to dopamine suppression. Furthermore, this dopamine signal predicted future song evolution, suggesting that dopamine drives behavior. This work showed for the first time that dopamine tracks the ups and downs of trial and error efforts that the animal produces while learning a natural skill, and bumps behavior in the right direction. Finally, they asked whether dopamine simply responds to rewarding signals– getting something right– or whether it tracks “reward prediction error”, the difference between what one just did and what one hoped to do. They directly demonstrated that the system compares its current performance with an expectation developed over the previous dozen renditions.